For a couple years, I’ve observed scores of developers making ill-informed claims about GraphQL. People have claimed that GraphQL allows the client to demand sorting, paging, and filtering from the server. People have claimed that GraphQL can result in execution of arbitrary queries or joins. People have claimed that GraphQL exposes too much power with not enough server-side control. As I hope to convey through this post, these claims are false.

Not long ago, I saw a tweet from someone making accusations about GraphQL. This tweet was from someone I respect and admire for their frequent display of depth and due diligence, which is why their statement surprised me. One of the replies on the thread was, “Graphql is a fancy name for odata 😉.” I took a deep breath and decided not to engage.

For a couple years, we’ve been using GraphQL with great success at SAP Concur. For a couple years, I’ve reflected on my past experience with OData and my happiness with GraphQL. For a couple years, I’ve sat idly by, trying not to jump in and say, “well, actually…”

Recently, I realized I had gathered most of my thoughts on GraphQL and I felt ready to present them. My irritation distilled down to a single declaration. Without knowing if anyone would take notice, but ready to have the conversation should anyone engage, I posted one simple tweet.

GraphQL is not OData. Can we please stop casting OData’s flaws onto GraphQL?

— Jeff Handley (@JeffHandley) August 29, 2018

At Microsoft, I used and propagated OData against my own judgment. I’m sorry I couldn’t stop the train wreck.

At Concur, we successfully employ GraphQL over top of RESTful APIs.

Feel free to @ me.

Experience with OData

I spent several years at Microsoft. I contributed to a few projects you might be familiar with:

- Silverlight UI SDK

- WCF RIA Services

- .NET Framework

- Visual Studio

- ASP.NET Web Pages

- Razor

- NuGet and the NuGet Gallery

WCF RIA Services

I had my first experience with OData while working on WCF RIA Services. I started as an SDE II on that project but eventually became the dev manager. WCF RIA Services brought Silverlight and ASP.NET together, allowing you to build Line-of-Business applications with ASP.NET domain/business layers and Silverlight UIs. This combination made it pretty easy to grow forms-over-data apps into business-logic heavy applications, keeping the business logic out of the UI through a clear separation of concerns.

WCF RIA Services allowed you to either expose your domain model directly to the client or create and expose a view model. By authoring CRUDE (create, read, update, delete, execute) operations and annotating them, you could easily create an API for your client to consume. But we needed a protocol for serializing requests and responses for those CRUDE operations and the data to go along with them. We ultimately landed on using some WCF primitives.

Before we solidifed our decision that we’d use WCF, our project was just called “RIA Services”, where RIA stood for “Rich Internet Application.” Using WCF resulted in prepending our project name with WCF and, believe it or not, getting reorged into the WCF group. This was all good though–to use WCF was far better than our proprietary protocol developed in our early preview releases.

WCF RIA Services was pretty well engineered. We were promoting a separation of concerns for applications built on our framework, and we ourselves kept our concerns separated. This led to both the server and the client being decoupled from the communication protocol. We were able to swap out that layer independently–largely because Wilco Bauwer is amazing. Wilco swapped out our proprietary protocol for WCF in days. And we demonstrated we could support multiple protocols in parallel.

Along came OData. Microsoft was pushing OData pretty hard for a while. Some really sharp folks in the SQL Server group invented it and OData had a lot of muscle behind it. It became clear that we needed to support OData for WCF RIA Services. After some long debates, we ultimately landed on the decision of:

- WCF RIA Services would support OData as an optional protocol

- But it would not use OData by default

We then created the OData protocol library in the WCF RIA Services SDK and made it easy for an application developer to swap out the default protocol for OData.

I don’t remember the arguments I had against OData during those debates, but I do remember one very specific incident that occurred after we shipped the SDK with OData support–a vulnerability in the OData specification that allowed remote code execution that could result in denial of service. You could kill an OData server with a single, well-crafted GET request. Oops.

NuGet

During a reorg, when ScottGu took on leadership in Azure, the ASP.NET group merged together with the WCF group. This opened up opportunities for projects like ASP.NET Web API. It also opened up an opportunity for me to expand my scope at Microsoft; I got to work on ASP.NET and NuGet.

I joined the NuGet team right as NuGet 1.5 was shipping. At that time, it was basically a side project, with everyone on the team also working on other products. NuGet was open source and the client was downloaded through CodePlex and installed as a Visual Studio extension.

NuGet, like every package manager, needed a public package repository. NuGet.org was built by our team, which happened to be the same folks working on ASP.NET MVC, ASP.NET Web Pages, Razor, and a few other products. Can you guess what protocol we were told we must use for the NuGet client to connect to the NuGet Gallery?

You guessed it: OData

I’ll save the details for when we get together over beers, but that choice didn’t work out very well and the team has been working to change course for years. Howard Dierking and I worked together on NuGet and we spent a significant portion of our time figuring out how to unwind OData out of NuGet.

Here are some reference blog posts that shed some light on the effort:

- A new search experience on the Gallery

- The NuGet.org Architecture

- NuGet.org Server Status

- Switching from WCF OData to Web API

Experience with GraphQL

I left Microsoft in 2015 and joined SAP Concur. Howard had joined Concur about 7 months before I did, working in a new Platform group led by Simon Guest.

Our group was embarking upon a monumental effort of re-engineering our UI. Concur’s legacy monolith had been built as a two-tier application with the UI talking directly to data sources (including databases). We needed to separate concerns, break the UI out of the monolith, start adopting modern UI technologies, and concentrate on building a scalable, user-friendly, accessible, maintainable UI layer.

We quickly selected Node and React as core technologies. We also studied the Flux architecture pattern that complemented React’s unidirectional data flow. We started using fluxible and other flux libraries, but when redux hit the scene, it took over.

Concur had already been breaking APIs out into microservices; we were a couple years into that journey when Howard and I joined. So how would we get our UI talking to the dozens of services?

You guessed it: OData

Just kidding. 😂

Filling a Gap

We were using fetchr pretty early on and it was pretty cool. Fetchr gave us a protocol and took care of a lot of plumbing, but it was very CRUD-oriented, which we didn’t love. We knew we wanted something to sit between our APIs and our UI that would serve as a façade, but we didn’t know what would fill that gap. Until GraphQL was announced.

As soon as GraphQL was available, Simon and Howard were all over it. They knew we needed to invest in using GraphQL; they saw the power of transforming the shapes coming out of our APIs into what our UI needs. They appreciated the simplicity of GraphQL’s protocol and its explicitness for both the client and the server. Simon and Howard recognized that our group could build the GraphQL layer independently from the groups building the APIs.

When Simon and Howard presented GraphQL to me, I was immediately sold. Within literally 5 minutes, the lightbulbs were going off for me and I was infatuated with GraphQL and ready to use it. We started putting plans in motion so that we could:

- Build, deploy, and operate a GraphQL server in Howard’s platform group

- Connect the new Node/React/Redux UI applications built in my group to GraphQL

- Design GraphQL schemas and resolvers that could be shared across mobile and web

- Connect the GraphQL server to the various microservices needed

- Even connect GraphQL to some legacy APIs where new APIs didn’t yet exist

- Innovate in the GraphQL layer at a pace independent from both the UI and the APIs

We’re more than two years into our experience using GraphQL at Concur. Overall, it’s been very positive. Sure, we’ve had our stumbles; we’re midstream on “version 2” of how we approach GraphQL organizationally. But we need version 2 for a great reason–the usage of it has outgrown the organizational structure we built around it. And as Conway’s law asserts, our implementation mimics the organizational structure, so the implementation will change in version 2 as well.

“organizations which design systems … are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.” –Melvin Conway, 1967

Decentralizing Development

When we first adopted GraphQL, it was a bit of an experiment. Simon, Howard, and I were all very optimistic about the prospect, and our teams were excited about the technology, but could it work at Concur? Howard created an “Orchestration Service” team that built the GraphQL server and implemented the schema and resolvers to meet the UI teams’ needs. They were serving the Web UI teams I work with as well as some of our Mobile teams. Overall, the work was relatively small–small enough that a single team could build it all.

This centralized model enforced the separation of concerns. The Orchestration Service team was not the same team building the APIs, and the Orchestration Service team was not the same team building the UI. They were a middle layer that integrated the UI with the APIs. They policed the GraphQL layer (as best as they could) to ensure it was not coupled to the implementation details of either the APIs or UIs and that the underlying APIs were approachable.

For the first 18 months or so of using GraphQL at Concur, this model worked out. We were making good progress both on product delivery and on breaking apart our monolith. But as the UI teams grew and took on more projects, we started realizing the Orchestration Service team could not keep up. We needed to scale out.

One of the Web UI teams in my group offered to contribute to the (Elixir) code base of Orchestration Service–we could send pull requests to add new schemas and resolvers. That marked the beginning of a decentralized development model. A year later, we are pivoting toward a GraphQL platform where UI engineering teams author Node.js resolver packages that get published to the runtime. Howard called it “Client Data Services” and the team has been aptly renamed.

Passionate

We’re feeling great about GraphQL and it has been a huge boost for our UI engineering teams as well as our API teams. This experience, coupled with my intimate experience with OData, is why I am so passionate about dispelling the myths around GraphQL’s likeness to OData. GraphQL is not OData.

GraphQL is not OData

My tweet asking if we could “please stop casting OData’s flaws onto GraphQL” indeed was noticed. Richard Dudley was the first to respond.

We are having the GraphQL vs OData discussion now, would love to hear some of the flaws in OData.

— Richard Dudley (@rj_dudley) August 29, 2018

The conversation took off from there. We talked about the flaws of OData, the positives of GraphQL, and the downsides of GraphQL too. We didn’t explicitly cover the positives of OData, but some of them came up in side threads. We’ll review all of these angles here.

Flaws in OData

In summary, OData was a way to serialize a SQL statement into a URL. When first applied, it gave too much power to the client, allowing it to use joins, where clauses, and sorting. A lot of that power can be dialed back now, but I still found it challenging to limit the exposure.

By opening up an OData endpoint, you lose control of what your clients are able to do and you don’t have explicit queries or use cases tracked. So when you need to change your schema, it becomes challenging to maintain backward compatibility with what your clients are doing.

It also becomes exceptionally difficult to optimize performance for any given use case because all execution runs through the same pipeline. Hooks were there to do it, but you have to process IQueryables in order to fulfill specific queries with tuned implementations. So when a client conducts a specific query and reports to you that performance is poor, you have to do really heavy lifting to address it. And in doing so, you can inadvertently disrupt other callers with similar but inexact scenarios/queries.

In many ways, OData queries result in remote code execution by design. My team and I had to address this specific security bulletin where specially-crafted GET requests could employ remote code execution to take down any public OData server: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/security-updates/SecurityBulletins/2013/ms13-007.

Positives about GraphQL

The server implements resolvers that fulfill specific graph queries—the client cannot ask for anything the server does not explicitly handle. The server returns only what the client asked for. No more, no less. No wasted bits over the wire.

APIs sitting behind GraphQL do not need to worry about serving every possible shape clients will want. Web wants more, mobile wants less? APIs don’t care. Clients ask for what they need. APIs return domain models. GraphQL transforms into view models.

The GraphQL layer can then specifically optimize queries over the RESTful APIs, minimizing API calls necessary to resolve a query. Yes, it is work to implement each resolver, but the explicitness is so liberating. And your clients have no idea what is happening behind the GraphQL façade. One call from the client could fan out to a dozen APIs (in a good way*). Orchestration stays out of the UI!

- Fanning out to a dozen APIs is good because it is still the server doing only what it was specifically built to do.

Howard, who authored the REST Fundamentals course on PluralSight, adds:

The same way that REST tamed the openness of the web through the formalization of constraints, GraphQL cleared up many ambiguities in REST by further constraining the uniform interface constraint.

We land in a mode where the UI code is dumb. So dumb. It is just using boring fetch calls and dealing with boring JSON responses that already match the desired shape so no boilerplate deserialization is necessary. And when as the RESTful services change, get combined or divided, it is even more boring because the clients don’t even have to accommodate it. You only update the affected resolvers in GraphQL and the client is completely oblivious. Yawn.

Another detail we have found important and highly successful: Our GraphQL layer is not implemented or operated by the teams building RESTful services. The UI teams build that layer and Howard’s team provides the platform and runs the service.

This lets the service teams concentrate on REST and the domain model. GraphQL is an implementation detail of the UI layer–a technology chosen by UI, not services. This has avoided the whole REST vs. GraphQL debate with each of the dozens of service teams building APIs. They get to do their thing the way they want. For all they care, the UI consumes their services directly. We just happen to put a GraphQL server in between. We can centralize the GraphQL implementation into a smaller community of developers where we can foster reuse and commonalities more easily.

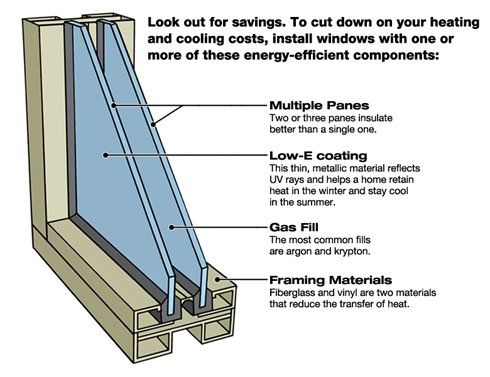

Service teams are not burdened with also knowing and doing GraphQL. If they had to, they would inevitably look for ways to skip a layer, violating the separation of concerns. I often refer to using GraphQL as a having a double-paned window. The UI cannot reach APIs directly; GraphQL is in between as insulation, reducing concerns on both sides. GraphQL helps both the UI and API layers as a result.

Service teams are not burdened with also knowing and doing GraphQL. If they had to, they would inevitably look for ways to skip a layer, violating the separation of concerns. I often refer to using GraphQL as a having a double-paned window. The UI cannot reach APIs directly; GraphQL is in between as insulation, reducing concerns on both sides. GraphQL helps both the UI and API layers as a result.

Downsides of GraphQL

Having to justify it when first adopting it or before enough service teams realize it will only benefit them.

It is indeed yet another layer of ceremony where every single UI interaction needs to be thought through and implemented specifically (or covered by existing resolvers).

It takes notable calendar time to design the schema thoughtfully such that it will have backwards compatibility as it grows over time. There is no versioning and the schema must be additive only (or with backwards compatible implementation detail changes). Breaking changes are possible, but you must phase it: add new schema, roll out compensating changes to ALL clients, remove old schema.

Howard adds:

I think this is the biggest stumbling block when starting a GraphQL effort - it forces you to think deeply about your data. Many organizations don’t realize this going in and are frustrated when the effort doesn’t work out or moves slowly.

It is yet another service to run and it is a single point of failure if not run well.

Features like paging and filtering and sorting are not built in and require that you invest in defining your patterns and reusable types.

For a big organization, you must intentionally create and foster a community of GraphQL contributors to ensure consistency and reuse. (Duplicating the same effort that should exist across API teams).

It works best when there is a single GraphQL server fulfilling the whole schema. That requires a single service that multiple teams can contribute resolvers to. That is where Howard’s team comes in for us–they build a platform we can publish resolver packages to.

Coordination between Service teams, GraphQL teams, consuming teams and multiple staging/integration environments can be challenging.

GraphQL, along with other strongly-typed modeling systems, doesn’t handle dynamic data very well. Concur supports “Custom Fields” and these features require exposing the normalized model in the schema, with field type information conveyed alongside the field values.

But I consider most of these to be human problems, not technology problems, and I like that trade-off.

Positives about OData

While the intent of the conversation was to dispell myths about GraphQL, many of the positive aspects of OData did come up.

It is better than every team choosing their own syntax for filter, expand, select and one team coosing hal another siren and a third json-ld

— Darrel Miller (@darrel_miller) August 30, 2018

I’d like to call out that Howard and Darrel co-authored a book titled Designing Evolvable Web APIs with ASP.NET along with Glenn Block, Pablo Cibraro, and Pedro Felix.

Darrel makes a good point about OData–it indeed standardized how to deal with several concerns. Paging, sorting, and filtering are a few important aspects. These features always go together because you cannot conduct them independently on different layers. If you perform paging and sorting on one layer, you must also do filtering there too, otherwise your paging will be broken. And when you are building a forms-over-data application with dozens, hundreds, or thousands of CRUD screens, OData can definitely accelerate development.

Rob Schlotman discussed his team’s successful use of OData.

On the non-hate side of things I used it with web api but put an additional api facade layer in front of it to control the surface area of our external api that clients used to avoid losing control. Gave us a data as svc layer that could scale on its own

— Rob Schlotman (@Schlotman) August 30, 2018

In his scenario, OData is an internal implementation detail providing a common data access layer. But they can side-step it where needed for optimization because the OData endpoint is not exposed to the clients.

For all simple / moderate gets we used odata . For complex actions (multi joins etc) we used custom actions with odata as the fall back, and then for unsupported odata things like search we would invoke a stored proc from odata

— Rob Schlotman (@Schlotman) August 30, 2018

Hans Olav brought up OData with ASP.NET Web API.

I think OData was great in web API. Though this was an OData with severely limited capabilities and I could restrict what functionality I needed. And all features were opt-in! Don't know GraphQL...

— Hans Olav (@HansOlavS) August 30, 2018

Indeed, by the time Web API was implementing OData, many lessons had been learned. OData endpoints need to be locked down by default instead of wide open.

Using OData

In my opinion, OData indeed still has a place where it’s valuable: as an implementation detail, serving as a data access layer for internal forms-over-data applications dealing with dozens, hundreds, or thousands of CRUD screens. In these scenarios, there’s often not any business logic to implement–you just need to be able to administer data through a UI, with a small number of users able to access the internal application.

But never as a public, internet-facing application. And not when there’s notable business logic involved or performance concerns that could arise based on creative paging, sorting, and filtering operations. And not as an API that other developers will write applications against that you won’t be able to control.

Using GraphQL

For GraphQL, Ken Horn drew a connection to the Backends For Frontends (BFF) pattern. I think it’s spot-on.

Could view it as a logical framework for creating a backend for frontend?

— SomeCallMeKen (@kenhorn) September 3, 2018

GraphQL really shines when it’s implemented as a middle layer between the UI and RESTful APIs. GraphQL is not going to replace REST; it complements it nicely.

Let your API teams build RESTful services that are ignorant of specific UI workflows–those APIs expose the domain model. Then the UI teams can build GraphQL schemas and resolvers that sit on top of those APIs and serve the custom-tailored view model for the UI workflows. Your Web/Mobile UIs then connect to GraphQL to get a single endpoint that orchestrates all of the API calls needed to fulfill the scenarios.

GraphQL is not OData

Jesse Ezell mentioned that some of the misconceptions about GraphQL come simply from GraphQL’s name. Developers who have worked with SQL and OData hear “query language” and think “SQL.” As Nick Schrock, co-creator of GraphQL, replied:

Naming is hard.

— Nick Schrock (@schrockn) August 29, 2018

I hope that this conversation helps us address the fear, uncertainty, and doubt with GraphQL. And I hope to see fewer people casting OData’s flaws onto GraphQL. While I understand how GraphQL can sound similar to OData on the surface, they are worlds apart.

Thanks

Thank you to Howard Dierking and Richard Dudley for their help on this post.