Disclaimer: The opinions expressed herein are my own personal opinions and do not represent my employer's view in any way.

It seems like the popular thing to do is to bash Microsoft for making so many classes and methods internal or private. It happens all the time. Sometimes the arguments are well-founded, sometimes they aren’t. There are many different opinions on this topic and many of them are valid even though they can be quite contradictory. The fact is though, this is a hard problem to solve, and Microsoft is solving it quite conservatively.

David Kean posted a response to Jeremy Miller as part of the latest debate on this topic. Ayende then posted a retort, expressing his dissatisfaction with David’s reasoning. But the common solution implied by Ayende and others would have its own pitfalls, and they could be much worse than the problems we have today with everything being locked down.

Ayende asserts:

The Microsoft backward compatibility strategy is a major reason why the default approach is to close down everything. Now, it is not as if there isn't a well defined way of saying: Touch that on your responsibility

He then continues:

But I think that this isn't actually the problem. The problem is that the rules that Microsoft has chosen to accept are broken. In that type of game, you are always losing. The only thing that you can do is to change the rate in which you are losing at.

What I infer from this post and others that criticize Microsoft for closing everything down, is that those customers would prefer for every class in the framework to be public, and every method to be virtual. Any class left internal, or any method left private, or anything that was sealed, would eventually come into the spotlight as the new poster-child for Microsoft’s inability to allow customers to extend the framework. So across the board, public virtual everything is the only way to cater to these desires.

Sounds very idealistic and even dreamy. But would it really be rainbows in the sky with pots of gold at the end? I don’t think so. I think we’d have much bigger problems on our hands.

Since backwards compatibility is in the crosshairs right now, I’ll weigh in on that too. As David discussed, we take backwards compatibility very seriously. Any public class or method is expected to be supported indefinitely. Ayende suggests that we ease up on this and cause a little pain for developers that are doing advanced things; they’ll likely be able to swallow the pill anyway. But the problem I see with this is that even a comment that states “This API supports the .NET Framework infrastructure and is not intended to be used directly from your code,” is not enough.

If this method or class is public, people will use it. Not just Einstein or Elvis, Mort will use this. In fact, Mort will likely use it before Einstein or Elvis does. Why? Because it will look like what he wants, it will behave like what he wants, and he might be more apt to use it as-is without searching for a better option. Maybe the better option doesn’t exist; would Mort create the better option on his own when a suitable solution already exists in the framework? Einstein or Elvis would probably think to at least wrap the implementation to abstract it away from the usage. Mort would not.

Now, when we destroy that method or class in vNext, we have major backwards compatibility problems on our hands. Who’s at fault? Mort’s boss will not know that Mort used a method that we warned him not to use… s/he will only know that Microsoft’s new .NET Framework broke their entire app and it’s going to cost them thousands, tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands of dollars to upgrade it. Heck with upgrading; the old framework works just fine. Just keep plugging away on the old version, stop innovating. And all of those sweet new features of the next version, sorry, you cannot use them—you have to implement them yourself. The problem we tried to allow you to avoid by making the class public has led you to face the exact same problem—you can’t use what we have already, so you have to implement it yourself.

I’ve been in the situation where I had the inability to upgrade an application to the new framework. It sucks. Bad. I ran a team that worked for years on a .NET 1.1 application. It’s a million lines of code, on .NET 1.1. It cannot be upgraded to .NET 2.0, 3.0, or 3.5. Why? Because ASP.NET 2.0 was not backwards compatible with ASP.NET 1.1. It was more along the lines of the 95% compatibility story. And it would be way too costly to update 700 ASPX files and 100 ASCX files to work in .NET 2.0+, let alone all of the regression testing necessary. And for what? At the end of the day, the application achieves the same features. So that project still lives in 1.1 and they have to create solutions to many of the problems that are addressed in the framework in .NET 2.0, 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0. Worst of all, the team is stuck in VS 2003. Yeah, it sucks.

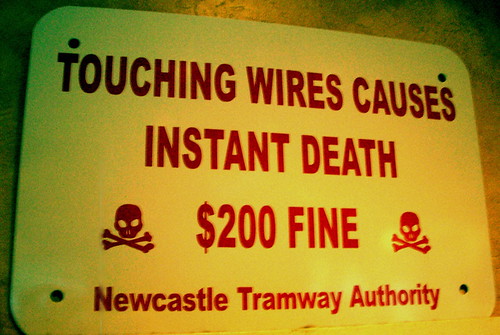

Public virtual ubiquity would fail for another reason too: support scoping. Ayende’s answer to warning developers not to touch XYZ was to put a comment on it saying it was for framework use only. Yeah, the framework does some of this already (and I know that I’ve called some of those methods). But David talked about how we put a lot of effort into our APIs to ensure that things are extensible where they can/need to me, and this effort could become quite a bit trickier. If everything is public/virtual, you still have to go through the same exercises and decide what to put the electric shock warning sign on. But now the problem isn’t as black and white—you’d be debating about tiny helper methods that only seem to make sense within a given context, wondering how that method might be useful for someone else on some other faraway land, writing some application that we’ve never thought of. This would completely erase the lines between API and implementation. And I find it strange that people would ask us to do this when all of the hip patterns these days are all about avoiding dependencies on internal implementations.

Public virtual ubiquity would fail for another reason too: support scoping. Ayende’s answer to warning developers not to touch XYZ was to put a comment on it saying it was for framework use only. Yeah, the framework does some of this already (and I know that I’ve called some of those methods). But David talked about how we put a lot of effort into our APIs to ensure that things are extensible where they can/need to me, and this effort could become quite a bit trickier. If everything is public/virtual, you still have to go through the same exercises and decide what to put the electric shock warning sign on. But now the problem isn’t as black and white—you’d be debating about tiny helper methods that only seem to make sense within a given context, wondering how that method might be useful for someone else on some other faraway land, writing some application that we’ve never thought of. This would completely erase the lines between API and implementation. And I find it strange that people would ask us to do this when all of the hip patterns these days are all about avoiding dependencies on internal implementations.

Some may think we’re coddling our customers by affording them backwards compatibility. And I bet that remark was implying that we’re coddling the Mort’s of the world instead of catering to the Einstein’s and Elvis’s, but I don’t see it that way at all. If we were coddling people, then we’d be letting them utilize our internal methods. Instead, we’re forcing people to re-implement things that we’ve already done, so that we can be more agile to change our implementations without causing harm. We do this at the cost of criticism by the few that would be able to protect themselves from said harm, when they are also those most-capable of re-implementing the solution.

Again, the opinions expressed herein are my own personal opinions and do not represent my employer's view in any way.